Our team had the opportunity to attend a Restorative Practice and Circles Training held by the San Diego County Office of Education (SDCOE) on Monday, September 10, 2018. The four presenters were Anthony Ceja (SDCOE), Phillip Lumula (GUHSD), Marc Barlow (GUHSD), and Ashley McGuire (IIRP Consultant). The materials were provided by the International Institute for Restorative Practices (IIRP).

What is normally a two-day training was condensed into a one-day professional development at Helix Charter High School. The professional development was brought to Helix with the intent to reinforce and increase the awareness of students' social-emotional needs while also providing tools and strategies to consider implementing.

We decided to participate in this professional development because we were interested in learning more about the implementation of restorative practices in the context of the high school setting.

Theoretical Foundation

Restorative practices have roots in ancient indigenous traditions found all over the world. In our modern society the practice has been defined as a collaborative process called conferencing. Family Group Conferencing (FGC) and Family Group Decision Making (FGDM) are two forms of counseling that use similar circles and principles. Theoretically, circles are a form of small group interventions intended to resolve conflict and build community.

Evidence-Based Practice

Organizations and individuals in fields such as education, social work, counseling, and criminal justice are combining theory, research and practice to develop restorative models that will measure positive outcomes. In education, circles and groups provide opportunities for students to share their feelings, build relationships and solve problems, and when there is wrongdoing, to play an active role in addressing the wrong and making things right (Riestenberg, 2002).

Counseling Intervention Techniques and Considerations

Restorative practices and circles can be incorporated into counseling techniques, which could be used preventatively or as a response to disruptive behavior and crisis. Teachers can use restorative circles to build relationships, trust, and an open environment among students within the classroom. Restorative practices can be used routinely, for example in the beginning of every class or at the end of every week, or as needed (such as one-on-one with a student who has broken class rules). We have observed Helix administrators utilize restorative questions when addressing student behavioral referrals. We have also observed Helix school counselors utilize restorative circles as a form of conflict mediation between students and among staff.

The training at Helix was geared towards all high school level students. The training was presented from the lens that students are expected to be at a developmental level where they can become aware of their behavior and the consequences it may have on others. Restorative practices welcomes all backgrounds because they are inclusive and allow all who are present to contribute to the conversation.

Although the training was focused on supporting older students, this practice is versatile. At the heart of restorative practices, it is seeking to understand rather than provide punitive punishment or one-sided leadership. One context restorative practices can be used in is with the entire class. In this form, a teacher or facilitator may use a restorative circle to allow students to take the lead in understanding a topic or resolving a large-scale issue. Another form it can take is in small group or individual conversations with a school counselor to acknowledge harm caused and rebuild trust that may have been lost.

A consideration a counselor must take into account is the severity of the conflict before implementing a restorative circle. For example, if the event is of a violent or abusive nature, other disciplinary measures could be considered. However, this does not mean that the healing power of a restorative circle cannot be used concurrently. Some circles may require an extensive amount of time to ensure that everyone has a chance to participate. Thus, one must be attentive of any time restrictions and number of participants. Lastly, we must educate our faculty and students on the philosophy, practice, and purpose of the group to encourage full buy-in and participation.

As future school counselors, we can incorporate this technique into our counseling practice by using restorative questions, which is one of the tools provided by SDCOE and IIRP. This tool is a small card that is double-sided. One side has questions to ask those who have caused harm and the other side includes questions to ask those who have been affected. This is a simple way to get in the habit of thinking in a restorative mindset. It does not take very long yet it allows students to feel heard and authority figures to better understand their students and the context of the situation.

Measuring Effectiveness

Both qualitative and quantitative methods could be used to measure outcomes. The restorative practices can be measured through the level of cohesion of a class or student perceived sense of safety through school-wide data, such as California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS). This is difficult to directly measure, but can be observed through interactions and a rising level of mutual support and individual initiative. It can also be measured through tracking the decrease of student referrals and the decrease in repeating offenders.

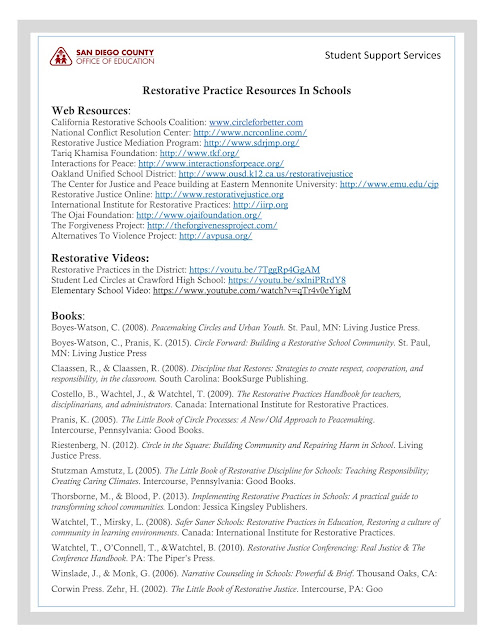

Additional Resources

Defining Restorative Article

Natalie Kutches, Melanie Lim, Juan Ugarte, & Jay Villafuerte

SDSU School Counseling Interns